MILWAUKEE–Ruby Rodriguez remembers the days when English class meant walking to her desk, talking to friends and checking the board.

Now class begins when her classmates’ names appear online. She sits alone at the dining room table, barefoot and petting the family dog. It’s her freshman year at St. Anthony High School, a private Catholic school in Milwaukee. She doesn’t know what her classmates look like, because nobody ever turns on their cameras.

After schools in Milwaukee went remote last March, Ruby and her friends in eighth grade at St. Anthony’s middle school missed their graduation ceremonies and parties. Her close friends attended different high schools, mostly other private schools that offered in-person instruction. St. Anthony, like many schools in urban areas, including Milwaukee Public Schools, started the fall semester online amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Virtual learning might be keeping Ruby, 14, and her family safer during a public health crisis. But it has made it exponentially harder for her to stay motivated and learn. Her online classes are lecture-heavy, repetitive and devoid of student conversation. Her grades have dropped from A’s and B’s to D’s and F’s. She stays up too late. She sleeps a lot. She misses her friends.

Like millions of students attending school virtually this year, Ruby is floundering academically, socially and emotionally. And as the pandemic heaves into a winter surge, a slew of new reports show alarming numbers of kids falling behind, failing classes or not showing up at all.

For months, experts hoped a return to classrooms would allow teachers to address the lapses in children’s academic and social needs. For many students, that hasn’t happened.

The goalposts are constantly shifting on a return to in-person learning, and abouthalf of U.S. studentsare attending virtual-only schools. It’s becoming increasingly clear that districts and states need to improve remote instruction and find a way to give individual kids special help online.

At the moment, plans to help students catch up are largely evolving, thin or nonexistent.

The consequences are most dire for low-income and minority children, who are more likely to be learning remotely and less likely to haveappropriate technologyandhome environmentsfor independent study compared with their wealthier peers. Children with disabilitiesandthose learning Englishhave particularly struggled in the absence of in-class instruction. Many of those students were already lagging academically before the pandemic. Now, they’re even further behind – with time running out to meet key academic benchmarks.

In high-poverty schools, 1 in 3 teachers report their students are significantly less prepared for grade-level work this year compared with last year, according to areportby the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research institution. Class failure rates have skyrocketed in school systems fromFairfax County, Virginia, toGreenville, South Carolina. Fewer kindergartenersmet early literacy targetsin Washington, D.C., this fall. And math achievement has dropped nationwide, according to a reportthat examined scores from 4.4 million elementary and middle school students.

“This is not going to be a problem that goes away as soon as the pandemic is over,” said Jimmy Sarakatsannis, leader of education practice at consulting firm McKinsey and Company. He co-wrote a report that estimated theaverage student could lose five to nine months of learning by June, with students of color losing more than that.

Beyond that, tens of thousands of children areunaccounted for altogether. Hillsborough County, Florida, started the year missing more than 7,000 students. Los Angeles saw kindergarten enrollmentdrop by about 6,000. There’s scant data about missing students’progress, of course, but few presume they’re charging ahead academically.

“We almost need a disaster plan for education,” said Sonya Thomas, executive director ofNashville Propel, a community group that works with many Black parents in Tennessee.

The Nashville school system offered some in-person learning in October and November beforereverting to all-virtual instructionafter Thanksgiving, as COVID-19 cases surged. Some parents say their children are failing every single subject, Thomas said.

Others say they still don’t have digital devices or high-speed internet, or that their children’s special-education learning plans aren’t being followed. One father said his middle school child struggles so much online that he walks out of the house and doesn’t come back until nighttime, Thomas said.

“Our parents are afraid their kids are falling behind, and they don’t know what the solution is,” Thomas said. “They’re looking for leadership. They’re looking for help.”

Abigail Alexander, right, a fifth grader at Head Middle Magnet School, helps her sister, Anaya, an exceptional education student at Maplewood High School, try to…

How much has learning slowed this year?

Nine months after COVID-19 shuttered schools and prompted the country’s largest experiment with virtual learning, the extent of academic regression is still a guessing game. And it looks different from student to student.

Johnny Murphy, 15, struggled for a month this fall to learn how to unmute himself during live video lessons with his class at Vaughn High School in Chicago. Murphy has autism and an intellectual disability.

His mother, Barbara Murphy, knows her son likely will never read beyond a third-grade level. But he’s backtracking on educational goals such as engaging with his peers and on life goals like leaving the house safely and using money, she said.

“It’s been like summer break all year.”

For Lily McCollum, 15, classes move more slowly online than they did in person. She’s a sophomore at Southridge High School in Kennewick, Washington, where she has been learning remotely all year.

“We’re probably the farthest behind in English and math,” she said. “It’s really hard to stay focused, especially if I don’t have my camera on.”

LaTricea Adams, founder ofBlack Millennials 4 Flintin Michigan, figures local children are at least a year behind in their studies, based on what she has heard from families and educators. Even before the pandemic, less than 30% of Flint’s third-grade students were proficient in English, according to the lateststate test scores.

“Some of these kids really need one-on-one sessions, but that’s almost impossible for them to get in a virtual setting,” Adams said.

Quantifying the extent of learning loss is difficult.

American students in third through eighth grade have held steady in reading but have fallen behind in math since last fall, according to a report this month by nonprofit testing organizationNWEA. The group examined academic progress in reading and math for 4.4 million students at 8,000 schools, with a big caveat: The students most likely to be tested were those attending classes in person, or attending schools with enough resources to test their remote learners.

In other words, the study makes the state of American education look better than it actually is, disproportionately reflecting the progress of students at higher-income schools who tend to score better on tests anyway.

Paraprofessional Jessica Wein helps Josh Nazzaro stay focussed while attending class virtually from his home in Wharton, N.J., on Nov. 18. The pandemic is threatening to wipe out the educational progress made by many of the nation’s 7 million students with disabilities, according to advocacy groups.

‘Kids are going feral’

A team of researchers at Stanford University crunched NWEA test scores for students in 17 states and the District of Columbia and reacheda more dire conclusion this fall. The average student had lost a third of a year to a full year’s worth of learning in reading, and about three-quarters of a year to more than a year in math since schools closed in March, the report estimated.

“Kids are going feral,” said Macke Raymond, director of theCenter for Research on Education Outcomesat Stanford University. “Thousands of them are unaccounted for, with no contact since schools have closed.”

The predictions are only estimates, and they’re built on the assumption thatstudents didn’t learn much at allbetween March and the start of this school year.

In any case, despite detailed findings for each school, some leaders in participating states have all but ignored the report.

Louisiana State Superintendent Cade Brumley said the report confirms what his department already suspected about learning loss. He said he has asked Louisiana school leaders to do their own diagnostic testing, but it’s not mandatory.

Brumley supports additional tutoring for students, but he’s wary of adopting flashy new programs. Teachers, he said, will do what they’ve always done to help students learn: deliver high-quality instruction with a high-quality curriculum.

In Arizona, one of the other participating states, education department officials said they were not familiar with the report.

Chaislynn Allen, 14, and her sister Addison, 17, attend the “AZ Open Our Schools Rally” with their family at the Arizona Capitol, advocating for in-person…

Tennessee posted the largest learning losses in reading, according to the report’s estimates.

Results varied within each state. For example, students at Tennessee’s wealthier schools didn’t lose much in reading achievement, or they pulled ahead of where researchers estimated they’d be. But students at the most impoverished schools fell behind – way behind, according to the estimates.

Penny Schwinn, Tennessee’s commissioner of education, said her team is concerned about those estimates.

Some children are doing fine, Schwinn said. But teachers tell her that low-income students and English learners are tracking behind where they would normally be this time of year.

TO READ THE RESTOF THIS ATICLE CLICK HERE

The Publishers of ALPHA-PHONICS hope this information will be of interest to our Blog Followers. We also hope Parents of public grade school students might consider teaching their OWN children to read. The information below can show them how many thousands of Parents have taught their OWN children to read, and they found it was much easier than they thought…..and less time consuming than they thought. Take a look:

WEBSITE TESTIMONIALS CATHY DUFFY REVIEW

OTHER REVIEWS AWARDS HOW TO ORDER

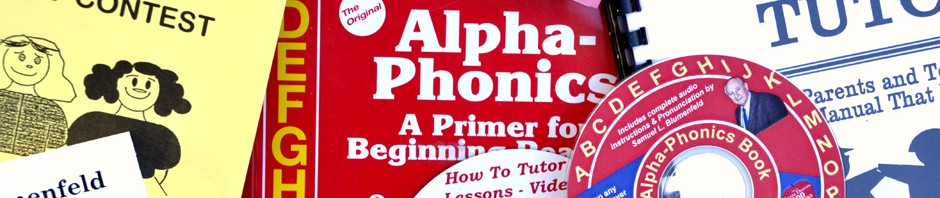

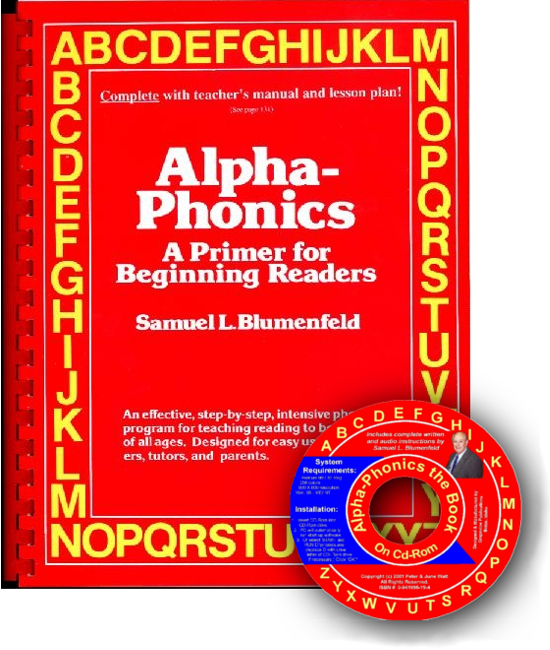

Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom

Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook