Pushback against this prejudice began in the Renaissance. The first person credited with the creation of a formal sign language for the hearing impaired was Pedro Ponce de León, a 16th-century Spanish Benedictine monk. His idea to use sign language was not a completely new idea. Native Americans used hand gestures to communicate with other tribes and to facilitate trade with Europeans. Benedictine monks had used them to convey messages during their daily periods of silence. (See also: New device translates brain activity into speech. Here’s how.)

Juan Pablo Bonet’s 1620 Reduction of the Letters of the Alphabet and Method of Teaching Deaf-Mutes to Speak provided detailed illustrations of signs.

Building on Ponce de León’s work, another Spanish cleric, priest and linguist Juan Pablo Bonet, continued exploring new communication methods. Bonet criticized some of the brutal methods that had been used to get deaf people to speak: “Sometimes they are put into casks in which the voice booms and reverberates. These violent measures are by no means to the purpose.”

In 1620 he published the first surviving work on the education of people with a hearing disability. Bonet proposed that deaf people learn to pronounce words and progressively construct meaningful phrases. The first step in this process was what he called the demonstrative alphabet, a manual system in which the right hand made shapes to represent each letter. This alphabet, very similar to the modern sign language alphabet, was based on the Aretina score, a system of musical notation created by Guido Aretinus, an Italian monk in the Middle Ages, to help singers sight-read music. The deaf person would learn to associate each letter of the alphabet with a phonetic sound. Bonet’s approach combined oralism—using sounds to communicate—with sign language. The system had its challenges, especially when learning the words for abstract terms, or intangible forms such as co junctions like “for,” “nor,” or “yet.”

In 1755 the French Catholic priest Charles-Michel de l’Épée established a more comprehensive method for educating the deaf, which culminated in the founding of the first public school for deaf children, the National Institute for Deaf-Mutes in Paris. Students came to the institute from all over France, bringing signs they had used to communicate with at home. Épée adapted these signs and added his own manual alphabet, creating a signing dictionary. Insistent that sign language needed to be a complete language, his system was complex enough to express prepositions, conjunctions, and other grammatical elements. Épée is known as the father of the deaf for his work and his establishment of 21 schools. (See also: Why the deaf have enhanced vision.)

Épée’s standardized sign language quickly spread across Europe and to the United States. In 1814 Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, a minister from Connecticut who wanted to teach his nine-year-old, hearing-impaired neighbor to communicate, went to France to train under Épée’s successor, Abbé Sicard. Three years later, Gallaudet established the American School for the Deaf in his hometown of Hartford, Connecticut. Students from across the United States attended, and just as at Épée’s school, they brought signs they used to communicate with at home. American Sign Languagebecame a combination of these signs and those from French Sign Language.

Thanks to the development of formal sign languages, people with hearing impairment can access spoken language in all its variety. The world’s many modern signing systems have different rules for pronunciation, word order, and grammar. New visual languages can even express regional accents to reflect the complexity and richness of local speech.

The publishers of ALPHA-PHONICS are pleased to bring this interesting story to the attention of its viewers. We hope you will invesigate our phonics reading program if you intend to teach a non-hearing impaired child to read. See links below:

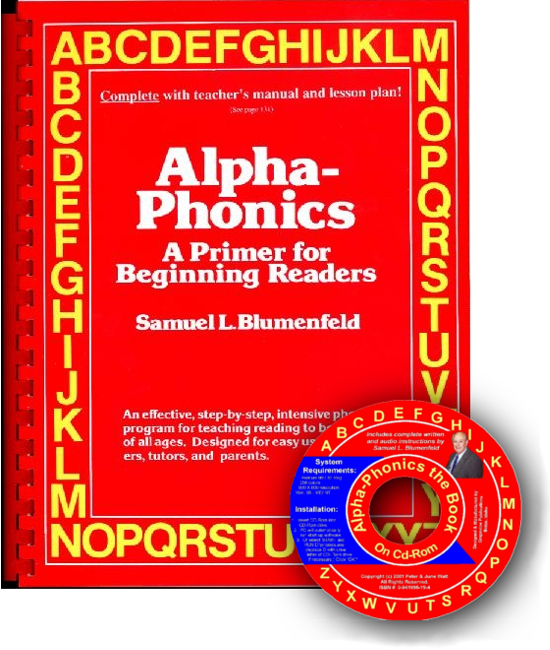

Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom

Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

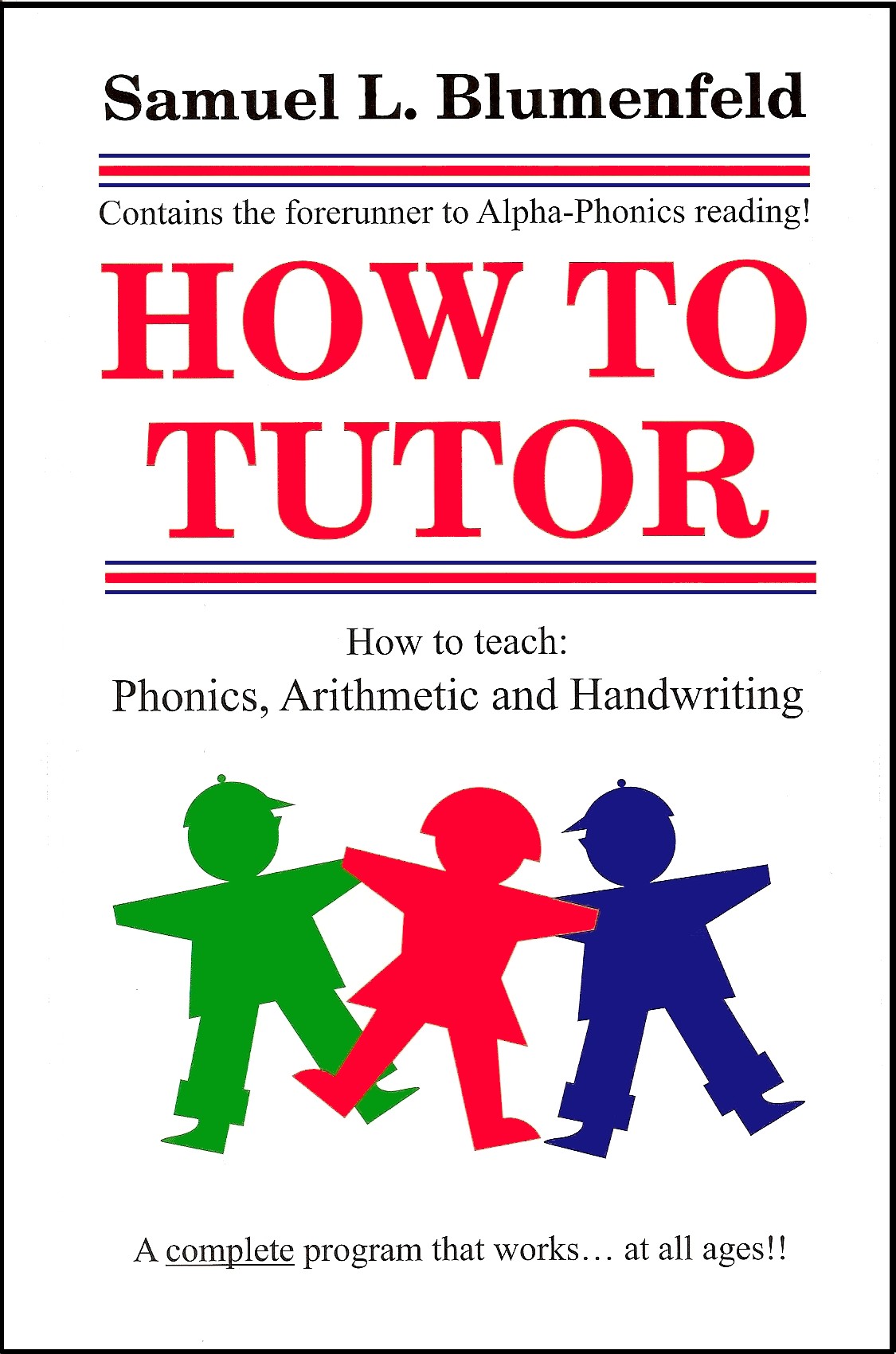

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook