A change in our diets may have changed the way we speak

You might be able to thank agriculture for a rise in the use of “f” and “v” sounds, a controversial new study suggests.

In a new study in Science, a team of linguists at the University of Zurich uses biomechanics and linguistic evidence to make the case that the rise of agriculture thousands of years ago increased the odds that populations would start to use sounds such as f and v. The idea is that agriculture introduced a range of softer foods into human diets, which altered how humans’ teeth and jaws wore down with age in ways that made these sounds slightly easier to produce.

“I hope our study will trigger a wider discussion on the fact that at least some aspects of language and speech—and I insist, some—need to be treated as we treat other complex human behaviors: laying between biology and culture,” says lead study author Damián Blasi.

If confirmed, the study would be among the first to show that a culturally induced change in human biology altered the arc of global languages. Blasi and his colleagues stress that changes in tooth wear didn’t guarantee changes in language, nor did they replace any other forces. Instead, they argue that the shift in tooth wear improved the odds of sounds such as f and v emerging. Some scientists in other fields, such as experts in tooth wear, are open to the idea. (Today, many scientists are racing to save languages that are dying out.)

Get science & environment stories, pictures, and special offers.

But many linguists have defaulted to skepticism, out of a broader concern about tracing

differences in languages back to differences in biology—a line of thinking within the field that has led to ethnocentrism or worse. Based on the world’s huge variety of tongues and dialects, most linguists now think that we all broadly share the same biological tools and sound-making abilities for spoken languages.

“We really need to know that the small [average] differences observed in studies like this aren’t swamped by the ordinary diversity within a community,” Adam Albright, a linguist at MIT who wasn’t involved with the study, says in an email.

Hockett’s case rested on a particular claim by C. Loring Brace, an influential anthropologist at the University of Michigan. A year after Hockett’s essay, Brace replied to say that he had changed his mind—causing Hockett to dismiss his own idea.

Hockett’s case rested on a particular claim by C. Loring Brace, an influential anthropologist at the University of Michigan. A year after Hockett’s essay, Brace replied to say that he had changed his mind—causing Hockett to dismiss his own idea.“We tried for months to show that this correlation didn’t exist … and then we thought, maybe there’s actually something there,” says study coauthor Steven Moran, a linguist at the University of Zurich.

The team then conducted follow-up analyses, including some that made use of a computer model of the face’s bones and muscles. The models found that it takes about 29 percent less energy to make labiodentals with an overbite than without.

Once f and v became less energetically expensive to make, Blasi’s team says, the sounds became more common—perhaps only accidentally at first, as people mis-vocalized sounds

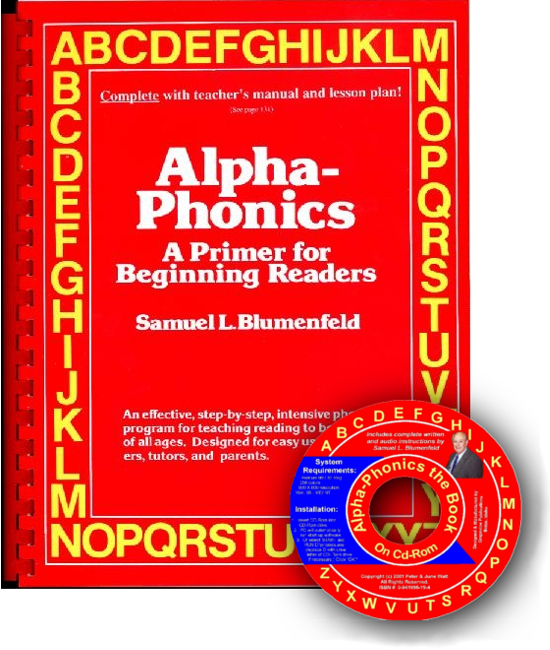

Alpha-Phonics phonics reading instruction program shown in new Mini Flash Drive version barely as large as a Postage Stamp

made by both lips touching, such as p or b, or what linguists call bilabials. But once labiodentals appeared, they stuck around, presumably because they’re usefully distinct. In English, the phrases “fever has gone global” and “Bieber has gone global” have very different meanings.

In English, the phrases “fever has gone global” and “Bieber has gone global” have very different meanings.

There is much more to this National Geographic article. Click here to Access the FULL story.

This full-time working Father, a Policeman, taught his own Son to read with Alpha-Phonics. Hear what Dad and Son have to say:

For detailed information about ALPHA-PHONICS use these LINKS:

Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook