This is an image of a full size T-Rex

New tiny tyrannosaur helps show how T. rex got big

The gangly predator fills in a crucial gap in our understanding of how tyrannosaurs came to dominate during the Cretaceous.

Now, a fossil found in Utah is helping paleontologists better understand how this region’s tyrannosaurs went from ecological paupers to princes. Weighing about 170 pounds and standing less than five feet tall, the newly named species Moros intrepidus is one of the smallest dinosaurs of its kind dating back to the Cretaceous period, the time between 66 million and 145 million years ago.

At 96 million years old, Moros is also the oldest Cretaceous tyrannosaur skeleton found in this region, pushing back that particular record by 15 million years. (Get the best look yet at the face of a tyrannosaur.)

A closeup shows the spine and tail bristles on an incredibly well-preserved fossil of the  herbivorous dinosaurPsittacosaurus mongoliensis, on display at the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt, Germany

herbivorous dinosaurPsittacosaurus mongoliensis, on display at the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt, Germany

Small wonder, then, that this dinosaur has the genus name Moros: the Greek embodiment of impending doom.

Out on a limb

At the dawn of the Cretaceous, tyrannosaurs were nowhere near the titans we imagine today. Instead, they were small, scrappy predators that hunted alongside much larger meat-eating dinosaurs called allosaurs. By 80 million years ago, North America’s allosaurs had faded, and tyrannosaurs had grown about 10 times larger—filling in the allosaurs’ apex niche in spectacular fashion.

It remains a mystery, though, how North America’s tyrannosaurs got big, since there’s a major gap in the continent’s mid-Cretaceous fossil record. With the exception of some isolated teeth, paleontologists had been missing skeletal evidence of North American tyrannosaurs from about 150 million years ago to 80 million years ago.

It remains a mystery, though, how North America’s tyrannosaurs got big, since there’s a major gap in the continent’s mid-Cretaceous fossil record. With the exception of some isolated teeth, paleontologists had been missing skeletal evidence of North American tyrannosaurs from about 150 million years ago to 80 million years ago.As a result, researchers including Zanno kept searching mid-Cretaceous rock formations. In 2013, Zanno struck gold: While walking through her field site in central Utah’s Cedar Mountain Formation, she unexpectedly saw limb bones jutting out of a hillside.

“We’ve been hunting in this area for 10 years, and these are the only bones of this animal we’ve ever recovered,” she says. “It takes teams a very, very long time and and an awful lot of luck.”

Dinosaur explorer

The foot bones of Moros are so skinny, it looks ganglier than even the juveniles of later, larger tyrannosaur species. But Moros was no toddler: Close study of the bones’ cross sections show that the dinosaur was at least six or seven years old when it died, making it close to adulthood.

The tiny fossil suggests that North America’s tyrannosaurs stayed small until at least the time of Moros, which means that tyrannosaurs grew to movie-monster size in just 16 million years—an evolutionary sprint. Perhaps fittingly, the Moros hind limb has some of the running-adapted features seen in later, bigger tyrannosaurs.

“Moros is important in that way; it’s the first hint of tyrannosaurs that eventually became the big ones,” says Thomas Carr, a paleontologist at Carthage College and a tyrannosaur expert who wasn’t involved with the study.

What’s more, Moros most closely resembles tyrannosaurs that lived in Asia in the early

Cretaceous. The find suggests that the ancestors of Moros crossed a land bridge from Asia into North America, as part of an exchange between the two continents that’s well-documented in other dinosaur groups. To honor its journey, researchers gave Moros the globe-trotting species name of intrepidus.

Now that her team has unveiled Moros, Zanno is eager to describe its swampy home. The same rocks that once held Moros also have yielded the massive allosaur Siats and several plant-eating dinosaurs, including some that are thought to have burrowed. She is also working with researchers to study the area’s fossil plant life.

Michael Greshko is a writer for National Geographic’s science desk.

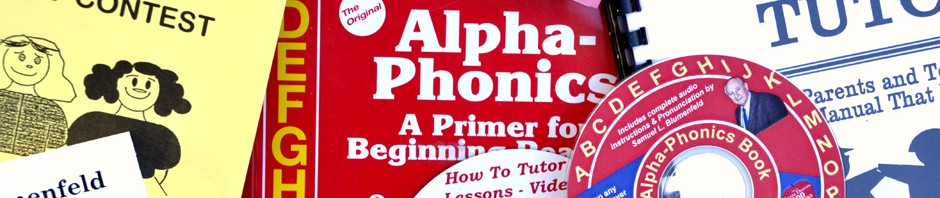

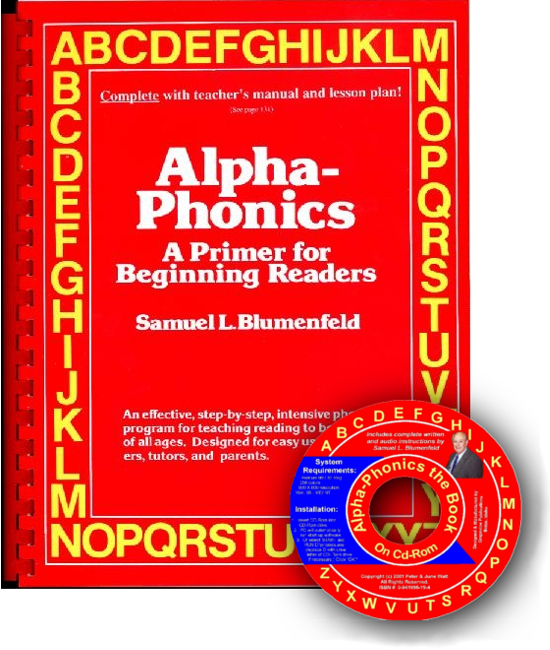

Alpha-Phonics

Alpha-Phonics The Alphabet Song!

The Alphabet Song! Water on the Floor

Water on the Floor Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom

Alpha-Phonics the Book on CD Rom Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test

Blumenfeld Oral Reading Assessment Test How To Tutor

How To Tutor How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook

How To Tutor Cursive Handwriting Workbook